For this blog post,

I decided to discuss an article by Dennis Crouch on patentlyo.com. The case

under review is Cohesive Tech. versus Water Corp. First, a brief background

about this case: This is a patent infringement case, where Cohesive accused

Water's 30 micrometer Oasis HPLC (high performance liquid chromatography)

columns to infringe their '874 patent in the first action and their '368 patent

in the second action. In the third action, Cohesive claimed Water's 25

micrometer Oasis HPLC columns to infringe both patents. Having used HPLC

before, I thought this case was interesting. For those of you who are new to

this field, HPLC is basically a process used to separate, identify, and measure

compounds in a liquid.

In the first action,

the jury decided that the '874 patent was valid and that the HPLC columns

infringed the patent. In the third action, the court was on Water's side (no

infringement). For the first two actions

(regarding the 30 micrometer HPLC column), the district court concluded that

"Waters failed to prove the deceptive intent necessary to sustain its

claim of inequitable product"[2].

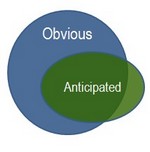

The article discusses the idea that novelty

and nonobviousness are "separate and distinct inquiries"[1]. See

figure 1. Dennis Crouch mentions how the Cohesive's

HPLC patent may be obvious, but was not anticipated. Water appealed and

argued that "the judgment was logically incorrect if anticipation truly is

the 'epitome of obviousness'. On appeal, the Federal Circuit confirmed that

novelty and obviousness are separate and distinct-- one does not necessarily follow

the other"[1]. Thus, it is important to realize that the tests for

anticipation and obviousness are different.

The confusion may

arise because it may seem that if there are references in the prior art (what

has already been done before) that anticipate a claim, it will usually mean

that the claim is obvious. However, two circumstances were suggested in which

the anticipated claim may still be nonobvious. The first circumstance is that

secondary considerations of nonobviousness may exist that are not relevant in

the anticipation claim in the prior art. I talked about these secondary

considerations in my previous blog post. The second circumstance suggested by

the court is when "although inherent elements apply in an anticipation,

inherence is generally not applicable to nonobviousness"[1].

The Patentlyo

article had a very good example, that I will copy below, because it really

helps in the understanding this idea:

“Consider, for example, a claim directed toward a

particular alloy of metal. The claimed metal alloy may have all the hallmarks

of a nonobvious invention—there was a long felt but resolved need for an alloy

with the properties of the claimed alloy, others may have tried and failed to

produce such an alloy, and, once disclosed, the claimed alloy may have received

high praise and seen commercial success. Nevertheless, there may be a

centuries-old alchemy textbook that, while not describing any metal alloys,

describes a method that, if practiced precisely, actually produces the claimed

alloy. While the prior art alchemy textbook inherently anticipates the claim

under § 102, the claim may not be said to be obvious under § 103.”

In contrast to

Figure 1, Judge Mayer thinks of the relationship between obviousness and

anticipation more closely to Figure 2, where anticipation is a subset of

nonobviousness. So what do you all think about this distinction between

anticipation and obviousness? Let me know in the comments below.

Figure 1 Figure 2

Links:

- http://patentlyo.com/patent/2008/10/nonobvious-yet.html

- http://www.finnegan.com/files/Publication/96c5dafa-fe96-4f24-b6e5-1172ae640ba5/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/c81948b7-039c-4bec-82d3-11dfb8dd620d/08-1029%2010-07-2008.pdf

Hi Manali, well done maintaining a high quality of work. Your blog is always an interesting read, with clearly articulated ideas and thoughtful choice of topics. Well done!

ReplyDeleteI love your diagrams that depict the difference between "anticipated" and "obvious" patents. It is really nice to see it explained in visual terms rather than via pages and pages of text, filled with legal jargon. As Professor Lavian already mentioned, I love reading your posts!

ReplyDelete