Monday, April 7, 2014

Sunday, April 6, 2014

Assignment 9: Blog Post 2: Anticipation versus Nonobviousness

For this blog post,

I decided to discuss an article by Dennis Crouch on patentlyo.com. The case

under review is Cohesive Tech. versus Water Corp. First, a brief background

about this case: This is a patent infringement case, where Cohesive accused

Water's 30 micrometer Oasis HPLC (high performance liquid chromatography)

columns to infringe their '874 patent in the first action and their '368 patent

in the second action. In the third action, Cohesive claimed Water's 25

micrometer Oasis HPLC columns to infringe both patents. Having used HPLC

before, I thought this case was interesting. For those of you who are new to

this field, HPLC is basically a process used to separate, identify, and measure

compounds in a liquid.

In the first action,

the jury decided that the '874 patent was valid and that the HPLC columns

infringed the patent. In the third action, the court was on Water's side (no

infringement). For the first two actions

(regarding the 30 micrometer HPLC column), the district court concluded that

"Waters failed to prove the deceptive intent necessary to sustain its

claim of inequitable product"[2].

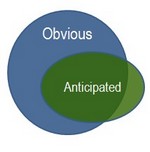

The article discusses the idea that novelty

and nonobviousness are "separate and distinct inquiries"[1]. See

figure 1. Dennis Crouch mentions how the Cohesive's

HPLC patent may be obvious, but was not anticipated. Water appealed and

argued that "the judgment was logically incorrect if anticipation truly is

the 'epitome of obviousness'. On appeal, the Federal Circuit confirmed that

novelty and obviousness are separate and distinct-- one does not necessarily follow

the other"[1]. Thus, it is important to realize that the tests for

anticipation and obviousness are different.

The confusion may

arise because it may seem that if there are references in the prior art (what

has already been done before) that anticipate a claim, it will usually mean

that the claim is obvious. However, two circumstances were suggested in which

the anticipated claim may still be nonobvious. The first circumstance is that

secondary considerations of nonobviousness may exist that are not relevant in

the anticipation claim in the prior art. I talked about these secondary

considerations in my previous blog post. The second circumstance suggested by

the court is when "although inherent elements apply in an anticipation,

inherence is generally not applicable to nonobviousness"[1].

The Patentlyo

article had a very good example, that I will copy below, because it really

helps in the understanding this idea:

“Consider, for example, a claim directed toward a

particular alloy of metal. The claimed metal alloy may have all the hallmarks

of a nonobvious invention—there was a long felt but resolved need for an alloy

with the properties of the claimed alloy, others may have tried and failed to

produce such an alloy, and, once disclosed, the claimed alloy may have received

high praise and seen commercial success. Nevertheless, there may be a

centuries-old alchemy textbook that, while not describing any metal alloys,

describes a method that, if practiced precisely, actually produces the claimed

alloy. While the prior art alchemy textbook inherently anticipates the claim

under § 102, the claim may not be said to be obvious under § 103.”

In contrast to

Figure 1, Judge Mayer thinks of the relationship between obviousness and

anticipation more closely to Figure 2, where anticipation is a subset of

nonobviousness. So what do you all think about this distinction between

anticipation and obviousness? Let me know in the comments below.

Figure 1 Figure 2

Links:

- http://patentlyo.com/patent/2008/10/nonobvious-yet.html

- http://www.finnegan.com/files/Publication/96c5dafa-fe96-4f24-b6e5-1172ae640ba5/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/c81948b7-039c-4bec-82d3-11dfb8dd620d/08-1029%2010-07-2008.pdf

Assignment 9: Blog Post 1: Obviousness, Graham Factors and Secondary Considerations

It seems that

determining whether or not something is obvious is very subjective. This is why

I feel that the patent system is like an art-- whoever can prove their case the

best wins.

In the Graham versus

John Deere case (1959), the Supreme Court decided that some basic criteria

should first be decided upon: "

- The scope and content of prior art

- The differences between the claimed invention and the prior art.

- The level of ordinary skill in the prior art"

I learned that the

top three criteria are known as Graham Factors, and the Supreme Court utilizes

them as controlling inquiries. The Supreme Court also uses "secondary

considerations" to argue non-obviousness. These considerations include: "

- Commercial Success

- Long-felt but unsolved needs

- Failure of others"

So what is this

supposed to mean? Let's just say a judge thought that a particular claim was

obvious. Again, this is very subjective, and while one judge may think that a

claim is obvious, another judge may not. But even if a specific claim seems

obvious to the examiner, the patentee can turn to the secondary considerations.

He or she "can present evidence that the invention has achieved commercial

success as a definite result of the invention". This suggests that it must

not have been obvious, because if it had been, it would have been done before

(as the need clearly existed). The patentee can present evidence that there was

a long-felt and unsolved need and that

others have tried and failed to solve this problem.

So now, the question

arises of where the patentee can get this evidence and how much evidence is

enough? Evidence can be acquired from the marketplace and from earlier patents

that may talk about the particular need and attempts to solve it. The decision

of whether the evidence is adequate is normally left to the judge.

I wanted to end with

this quote, because I thought was interesting:

"…this question

[regarding obviousness] remains a fairly subjective sandbox- and this is a

sandbox that patent practitioners earn their money in-- because it

sometimes takes concise and strong

arguments to reverse a obviousness rejection"[1].

Links:

Saturday, April 5, 2014

Friday, April 4, 2014

Assignment 8: Extra Credit Blog Post 1: Reading through a Patent

Hi all! So there has

been a lot of talk about patents in general (their purpose, function, etc) ,

and in class, we have read through and analyzed claims for certain patents. I

think this is an extremely important skill and I wanted to practice it myself more.

The patent that I

chose to analyze is titled, "Portable blood filtration devices, systems,

and methods," and can be found in the link below. The reason I chose this patent was that I was

at an event this Wednesday where co-founders of start-ups were pitching their

companies. One co-founder talked about his product, the chemofilter, which is a

catheter based filter that can be placed into a vein that is draining a target

organ (i.e. liver) to be able to trap all the excess toxic chemo drugs before

they go back to the heart and are pumped to the rest of the body. Since this

reduces systemic toxicity, it allows the doctor to deliver a high dose of

chemotherapy. The thing that stood out to me was that the co-founder mentioned

something along the lines of how most patents in the market were for putting

things in the body, and since they were dealing with flow going away from the

organ, they could file a broad patent, which is extremely useful. I also

thought it was interesting how he mentioned this fact in his pitch to a VC,

because it shows how much of an

advantage broad patents can give you.

Okay, now to

analyzing a few claims of this patent. Here are some key points that I learned/

ideas and questions that went through my head:

- The abstract shows that this patent protects a "device, system, and method"[1]. To me, a device and a system are very similar (or perhaps there is a difference?). I also wondered why they didn't have two separate patents-- one for the device and one for the method.

- I also noticed the use of more ambiguous wording, such as "selectively remove or reduce" [1].

- While it is important to define certain aspects of the product, it is also important to keep it general. So for example, they needed to define the unwanted substance that needs to be filtered. However, the patentees did not want to limit themselves in doing so. Thus, they said, "The unwanted substance includes one or more of a pathogen, a toxin, an activated cell, and an administered drug" [1]. Notice how they cannot use words such as "etc." because that is too ambiguous and anything can fall underneath that category.

- There was a "FIELD" section that was one sentence long and basically mentioned that this patent involved "the selective removal of unwanted components" [1]. If I worked at the USPTO and had to read through many patents, this would be a good section for me to come to first when initially sorting through patents.

- There was a "BACKGROUND" section that talked about why this is important. I think this section is good for the general reader, because it mentioned why this product is important, and talked about sepsis (blood infection) that can lead to organ dysfunction, death, and limb amputation. So, why is it important to include a section like this? I think it makes it easier for those who are judging the validity of a patent to see how important or vital it is in the larger scope. Yes, they could have looked up this information themselves online, but most of the jury will not have the motivation to do so. It is important to note that most of the jury, especially in certain courts, are less educated and also less interested. Some people just serve on the jury because it is a requirement for them, and not because they are genuinely interested in the case.

- After reading the claims on the patent, some important aspects are:

- This protects a method for extracorporeal treatment, meaning the blood is filtered outside the body

- To filter, a microfluidic channel is used, and the channel has microsieve wall filters.

- The shape of the microfluidic channel is rectilinear. I thought it was interesting how the dimensions were stated: depth of no more than 200 microns and width of at least 10x the depth. Thus, this patent protects a range of dimensions.

- The removal of unwanted substances can also be done using cascade filtration with multiple membranes of different pore sizes or using an adsorbent.

- I realized many of the claims, especially claims 4 to 13, consisted of filtration methods that already existed, but to make this new, they linked it to the earlier claims, saying "The method of any of the above claims, …" For example, extracting by binding the unwanted substance to an adsorbent has already been done before and is most likely patented.

- At the very beginning of this blog, I mentioned that this patent protects a device, system, and method. While claims 1-14 are all on the method, claim 15 is, "A device configured to implement any of the foregoing methods" and claim 16 is "A system for implementing any of the foregoing methods".

Overall, I think I

am getting slightly better at reading patents, or maybe I just happened to find

this patent not so difficult to decipher. I also think it is a really good

exercise to continue!

Link:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)