Saturday, May 3, 2014

Assignment 12, Blog Post 2: Experience integrating Social Media in the Class

Prompt: Please talk about your experience of using social

media tools for learning, how you used the blog, YouTube, and comments, how

they are different from traditional learning tools, what is the value of using

these tools, and how you can do it even better.

I learned so much from interacting with others, and thus, I

really enjoyed the interactive component of this class. We learn so much from

our peers. Also, overtime, I got comfortable with talking in front of the

webcam and making videos of the material. I enjoy filming myself in general, so

I also really liked that aspect of the class. I thought it was really nice to

have the online component paired with the offline component (discussions in

class). I also think that listening to other student’s videos allowed us to get

to know other students and their interests better, and this also facilitated

having the conversations in class. Social media is convenient because it allows

people to be in different places at different times and still communicate

effectively. I do think I spent a lot of time doing the blogs and making them

detailed. I think something that I can improve on is tying concepts from

different blogs together. I did do that several times (such as with

evergreening of pharmaceuticals), but finding more connections would be nice. I

really hope everyone enjoys reading my blog, because I sure enjoyed reading

everyone else's blogs! J

Good luck on finals everyone!

Assignment 12, Blog Post 1: Experience in the Class

Prompt: Please describe your experience in the class, what

you learned, why this is important to you, what is the value, and in general,

how the knowledge from this class would help you in the future.

I really enjoyed this class! After my undergraduate

education, I want to go into industry for a bit, and I feel that it gave me a unique

perspective on industry and the competition that takes place over inventions. I

feel that I could not have learned about this in as much detail in my other

classes, and thus, taking a class geared towards patents was extremely

insightful. I do hope to invent medical devices (or be part of a team that does

so), and thus knowing how to file for a patent, what can be patented, and how

the entire system works is very useful. I know for a fact that all the

knowledge that I learned in this class is not going to go to waste, but I also

need to be proactive in keeping up with changes in the system. Since I am

interested in the medical devices/ biotech area, I want to also learn more

about FDA regulations. Thanks so much for a great semester!

Assignment 11, Blog Post 2: Silly Patents-- Hands Free Towel Carrying System

The second silly patent I want to talk about is the Hands

Free Towel Carrying System. Here is a brief description:

“A towel of a generally rectangular configuration comprised of

an absorbent material has a loose end, a parallel coupling end, a pair of side

edges and a generally cylindrical neck loop comprised of an elastomeric

material.”[1]

Here are some images:

On the patent, it says that the reason (or more

appropriately, motivation) to have a hands free towel carrying system is to

prevent loss, theft, and contamination. I feel that perhaps this invention

could be useful for someone who goes swimming regularly, and doesn’t want to

lose his or her towel. And I do also understand the contamination problem,

since a large towel is used to wipe all areas of the body and you definitely do

not want to share your towel with a stranger! But I do think that there are

other easier ways to solve these problems! For example, you can just get a

really unique towel with an interesting color pattern. That would also make

your life less bland J

And personally, I would get annoyed of having a towel hanging around my neck

like that, because I would imagine that it would get kind of heavy after a

while. Plus, when would one need this? Definitely not at one’s house. Maybe at

the beach or swimming pool? I am not sure if there would be a social stigma of

carrying a towel like that at the beach. I feel that all these factors need to

be taken into account, because there is no point in inventing something if

nobody is going to use it. This patent also talks about prior art as if the

inventor is attempting to prove that this exact system has not been invented

before. Also interestingly, this patent was published in 2004—wow! I can’t

believe it took so long for somebody to come up with such a simple system. [1] Let’s

look at the criteria now:

Non-obviousness: Hmm…personally, I found this pretty

obvious. Normally, if people want to carry their towel with no hands, they just

throw it around their neck. This is doing something similar, but with something

that looks more like a necklace.

Novelty: I think this could be debatable. I’m sure something

similar must have been thought about before. In fact, in the top picture, it

almost looks like a dress! (some dresses are designed very similarly).

Enablement: I honestly just can’t see a lot of people

buying this, because there isn’t a huge need for this. Even during the time I

was a swimmer, I haven’t heard too many people complain about losing their

towels or worrying about contamination.

Usefulness: Yes, it is useful because it does what it

says it does!

[1] https://www.google.com/patents/US6718554?dq=6718554&hl=en&sa=X&ei=g2JlU8amF8fI8gHhooC4Dw&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA

Assignment 11, Blog Post 1: Silly Patents- Device for the Treatment of Hiccups

The first silly patent that I want to talk about is titled,

“Device for the treatment of hiccups”. The patent number is US 7062320 B2. I

was interested in this because it had a biological aspect to it. This device

treats hiccups by “galvanic stimulation of the Perficial Phrenetic and Vagus

nerves using an electric current”. In the background portion of the patent, the

inventor mentions that the invention relates not just to a method and an apparatus

for the treatment. The reason why I though this patent is so crazy is because

everyone knows that hiccups go away after drinking water. So this got me

thinking what causes hiccups? My guess was that a lack of sufficient water

intake may cause hiccups, but I decided to check WebMD to see what they had to

say. According to WebMD, “A very full stomach can cause bouts of hiccups that

go away on their own. A full stomach can be caused by: Eating too much food too

quickly, drinking too much alcohol, swallowing too much air, smoking, a sudden

change in stomach temperature, emotional stress or excitement”. [2] Anyways,

that is beside the point—I just thought it was pretty interesting. The point is

that age-old cure for hiccups is so simple and natural. In modern society

(unless we are in the desert), it is so easy to find water. And usually hiccups

go away right after you drink a couple sips. When I was young, one of my

childhood friends told me that when I get hiccups, I should take a sip of water

with my head in between my legs (so upside down)—and for the longest time I

believed that and followed diligently.

Let’s see if this patent falls can be considered a valid

patent based on the criteria:

Non-obvious: This would also get a pass. It definitely is

not the obvious way of curing hiccups!

Novelty: I would give this a pass, as I don’t believe this

has been thought of or implemented before.

Enablement: I don’t think many people would buy this! It

wouldn’t do so well in industry, because people would probably be more afraid

of getting shocked than

Usefulness: Well, first of all, let’s just assume this works

and does in fact cure hiccups. Then, it is useful, but I don’t know how many

people would actually use it. Look’s like the biggest problem we have here is

enablement!

[1] https://www.google.com/patents/US7062320?dq=7062320&hl=en&sa=X&ei=VhVkU_bMKsO98gH0kIHICg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAA

[2] http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/tc/hiccups-topic-overview

Friday, May 2, 2014

Assignment 10: Blog Post 1: Public Health and Patents

There

is a general debate on whether patents are incentivizing or hurting innovation

in various industries. Here, I want to focus on medical care, including

pharmaceuticals and medical devices. It is well known that developing drugs

requires a large amount of investment from long term research and expensive

clinical trials. So what incentivizes the development of drugs, other than the

desire and need to treat and cure diseases? Some would say it is the protection

offered by patents that allows pharma companies to gain a financial return on

their investments. However, there is another side to the story, as some argue

that patents are holding back medical research, since researchers can no longer

access patented materials or methods. Another con due to patents is that they

are responsible for the increased prices of essential medicines in developing

countries.

I

read an article that was published in January 2010 by E. Richard Gold, et al.

In both high and low income countries, existing patents increase the cost of

medicines. But what about other services, such as diagnostics? For other

services, is usually depends on whether the newly patented medicines turn out

to be cheaper than those that are existing or not. Overall, the patent system

has resulted in a huge increase in healthcare costs and decreasing levels of

innovation. Overall healthcare costs are increasing rapidly, but the fastest

growing sector of these costs are pharmaceutical products. A shockingly

surprising fact is that "the cost of developing new medicine from

discovery through clinical trials appears to double every decade. Yet, …

industry is producing fewer new drugs every year of which a declining

percentage is truly innovative"[1]. As I mentioned in my earlier blog post

with drug patent evergreening, many new patents are just on small changes to

existing drugs. It is essential to find a balance between the rights of patent

owners and the general public needs. Patents in the public health arena are

really interesting because the financial incentives provided by patents is not enough

to assure that products in areas such as neglected diseases will be pursued [2].

What changes do you think need to be implemented in the patent system to

account for this?

Links:

Monday, April 7, 2014

Sunday, April 6, 2014

Assignment 9: Blog Post 2: Anticipation versus Nonobviousness

For this blog post,

I decided to discuss an article by Dennis Crouch on patentlyo.com. The case

under review is Cohesive Tech. versus Water Corp. First, a brief background

about this case: This is a patent infringement case, where Cohesive accused

Water's 30 micrometer Oasis HPLC (high performance liquid chromatography)

columns to infringe their '874 patent in the first action and their '368 patent

in the second action. In the third action, Cohesive claimed Water's 25

micrometer Oasis HPLC columns to infringe both patents. Having used HPLC

before, I thought this case was interesting. For those of you who are new to

this field, HPLC is basically a process used to separate, identify, and measure

compounds in a liquid.

In the first action,

the jury decided that the '874 patent was valid and that the HPLC columns

infringed the patent. In the third action, the court was on Water's side (no

infringement). For the first two actions

(regarding the 30 micrometer HPLC column), the district court concluded that

"Waters failed to prove the deceptive intent necessary to sustain its

claim of inequitable product"[2].

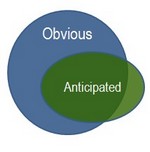

The article discusses the idea that novelty

and nonobviousness are "separate and distinct inquiries"[1]. See

figure 1. Dennis Crouch mentions how the Cohesive's

HPLC patent may be obvious, but was not anticipated. Water appealed and

argued that "the judgment was logically incorrect if anticipation truly is

the 'epitome of obviousness'. On appeal, the Federal Circuit confirmed that

novelty and obviousness are separate and distinct-- one does not necessarily follow

the other"[1]. Thus, it is important to realize that the tests for

anticipation and obviousness are different.

The confusion may

arise because it may seem that if there are references in the prior art (what

has already been done before) that anticipate a claim, it will usually mean

that the claim is obvious. However, two circumstances were suggested in which

the anticipated claim may still be nonobvious. The first circumstance is that

secondary considerations of nonobviousness may exist that are not relevant in

the anticipation claim in the prior art. I talked about these secondary

considerations in my previous blog post. The second circumstance suggested by

the court is when "although inherent elements apply in an anticipation,

inherence is generally not applicable to nonobviousness"[1].

The Patentlyo

article had a very good example, that I will copy below, because it really

helps in the understanding this idea:

“Consider, for example, a claim directed toward a

particular alloy of metal. The claimed metal alloy may have all the hallmarks

of a nonobvious invention—there was a long felt but resolved need for an alloy

with the properties of the claimed alloy, others may have tried and failed to

produce such an alloy, and, once disclosed, the claimed alloy may have received

high praise and seen commercial success. Nevertheless, there may be a

centuries-old alchemy textbook that, while not describing any metal alloys,

describes a method that, if practiced precisely, actually produces the claimed

alloy. While the prior art alchemy textbook inherently anticipates the claim

under § 102, the claim may not be said to be obvious under § 103.”

In contrast to

Figure 1, Judge Mayer thinks of the relationship between obviousness and

anticipation more closely to Figure 2, where anticipation is a subset of

nonobviousness. So what do you all think about this distinction between

anticipation and obviousness? Let me know in the comments below.

Figure 1 Figure 2

Links:

- http://patentlyo.com/patent/2008/10/nonobvious-yet.html

- http://www.finnegan.com/files/Publication/96c5dafa-fe96-4f24-b6e5-1172ae640ba5/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/c81948b7-039c-4bec-82d3-11dfb8dd620d/08-1029%2010-07-2008.pdf

Assignment 9: Blog Post 1: Obviousness, Graham Factors and Secondary Considerations

It seems that

determining whether or not something is obvious is very subjective. This is why

I feel that the patent system is like an art-- whoever can prove their case the

best wins.

In the Graham versus

John Deere case (1959), the Supreme Court decided that some basic criteria

should first be decided upon: "

- The scope and content of prior art

- The differences between the claimed invention and the prior art.

- The level of ordinary skill in the prior art"

I learned that the

top three criteria are known as Graham Factors, and the Supreme Court utilizes

them as controlling inquiries. The Supreme Court also uses "secondary

considerations" to argue non-obviousness. These considerations include: "

- Commercial Success

- Long-felt but unsolved needs

- Failure of others"

So what is this

supposed to mean? Let's just say a judge thought that a particular claim was

obvious. Again, this is very subjective, and while one judge may think that a

claim is obvious, another judge may not. But even if a specific claim seems

obvious to the examiner, the patentee can turn to the secondary considerations.

He or she "can present evidence that the invention has achieved commercial

success as a definite result of the invention". This suggests that it must

not have been obvious, because if it had been, it would have been done before

(as the need clearly existed). The patentee can present evidence that there was

a long-felt and unsolved need and that

others have tried and failed to solve this problem.

So now, the question

arises of where the patentee can get this evidence and how much evidence is

enough? Evidence can be acquired from the marketplace and from earlier patents

that may talk about the particular need and attempts to solve it. The decision

of whether the evidence is adequate is normally left to the judge.

I wanted to end with

this quote, because I thought was interesting:

"…this question

[regarding obviousness] remains a fairly subjective sandbox- and this is a

sandbox that patent practitioners earn their money in-- because it

sometimes takes concise and strong

arguments to reverse a obviousness rejection"[1].

Links:

Saturday, April 5, 2014

Friday, April 4, 2014

Assignment 8: Extra Credit Blog Post 1: Reading through a Patent

Hi all! So there has

been a lot of talk about patents in general (their purpose, function, etc) ,

and in class, we have read through and analyzed claims for certain patents. I

think this is an extremely important skill and I wanted to practice it myself more.

The patent that I

chose to analyze is titled, "Portable blood filtration devices, systems,

and methods," and can be found in the link below. The reason I chose this patent was that I was

at an event this Wednesday where co-founders of start-ups were pitching their

companies. One co-founder talked about his product, the chemofilter, which is a

catheter based filter that can be placed into a vein that is draining a target

organ (i.e. liver) to be able to trap all the excess toxic chemo drugs before

they go back to the heart and are pumped to the rest of the body. Since this

reduces systemic toxicity, it allows the doctor to deliver a high dose of

chemotherapy. The thing that stood out to me was that the co-founder mentioned

something along the lines of how most patents in the market were for putting

things in the body, and since they were dealing with flow going away from the

organ, they could file a broad patent, which is extremely useful. I also

thought it was interesting how he mentioned this fact in his pitch to a VC,

because it shows how much of an

advantage broad patents can give you.

Okay, now to

analyzing a few claims of this patent. Here are some key points that I learned/

ideas and questions that went through my head:

- The abstract shows that this patent protects a "device, system, and method"[1]. To me, a device and a system are very similar (or perhaps there is a difference?). I also wondered why they didn't have two separate patents-- one for the device and one for the method.

- I also noticed the use of more ambiguous wording, such as "selectively remove or reduce" [1].

- While it is important to define certain aspects of the product, it is also important to keep it general. So for example, they needed to define the unwanted substance that needs to be filtered. However, the patentees did not want to limit themselves in doing so. Thus, they said, "The unwanted substance includes one or more of a pathogen, a toxin, an activated cell, and an administered drug" [1]. Notice how they cannot use words such as "etc." because that is too ambiguous and anything can fall underneath that category.

- There was a "FIELD" section that was one sentence long and basically mentioned that this patent involved "the selective removal of unwanted components" [1]. If I worked at the USPTO and had to read through many patents, this would be a good section for me to come to first when initially sorting through patents.

- There was a "BACKGROUND" section that talked about why this is important. I think this section is good for the general reader, because it mentioned why this product is important, and talked about sepsis (blood infection) that can lead to organ dysfunction, death, and limb amputation. So, why is it important to include a section like this? I think it makes it easier for those who are judging the validity of a patent to see how important or vital it is in the larger scope. Yes, they could have looked up this information themselves online, but most of the jury will not have the motivation to do so. It is important to note that most of the jury, especially in certain courts, are less educated and also less interested. Some people just serve on the jury because it is a requirement for them, and not because they are genuinely interested in the case.

- After reading the claims on the patent, some important aspects are:

- This protects a method for extracorporeal treatment, meaning the blood is filtered outside the body

- To filter, a microfluidic channel is used, and the channel has microsieve wall filters.

- The shape of the microfluidic channel is rectilinear. I thought it was interesting how the dimensions were stated: depth of no more than 200 microns and width of at least 10x the depth. Thus, this patent protects a range of dimensions.

- The removal of unwanted substances can also be done using cascade filtration with multiple membranes of different pore sizes or using an adsorbent.

- I realized many of the claims, especially claims 4 to 13, consisted of filtration methods that already existed, but to make this new, they linked it to the earlier claims, saying "The method of any of the above claims, …" For example, extracting by binding the unwanted substance to an adsorbent has already been done before and is most likely patented.

- At the very beginning of this blog, I mentioned that this patent protects a device, system, and method. While claims 1-14 are all on the method, claim 15 is, "A device configured to implement any of the foregoing methods" and claim 16 is "A system for implementing any of the foregoing methods".

Overall, I think I

am getting slightly better at reading patents, or maybe I just happened to find

this patent not so difficult to decipher. I also think it is a really good

exercise to continue!

Link:

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Assignment 7, Blog Post 2: USPTO Guidelines on Determining Obviousness

Since this week's

assignment was to talk about obviousness, I wanted to go over some of USPTO's

guidelines for determining obviousness.

As Professor Lavian mentioned in class, some law schools, such as

Stanford, have an entire course on obviousness! In 2010, USPTO released a set

of updated guidelines on determining obviousness. In link [1] below, you can

find a table from the Federal Register that talks about "Combining Prior

Art Elements", "Substituting One Known Element for Another",

"The Obvious to Try Rationale",

and "Consideration of Evidence".

Here, I will briefly

summarize some of the facts that I learned:

-- Even when there

exists a general method to make the claimed product and this method can be used

by an ordinary artisan, the claim is still nonobvious if the suggested use of

the method had not been known before.

-- The claimed

invention is likely to be obvious if the inventor combines elements from prior

art that would reasonably have been expected to maintain their respective

properties or functions after they have been combined. While this may seem

self-evident, I think it is good to state explicitly. Here, the question that arises is how one

would define reasonable.

-- "When

determining whether a reference to a different field of endeavor may be used to

support a case of obviousness (i.e. is analogous), it is necessary to consider

the problem to be solved." The professor talked about this in class as

well: For example, a processor can refer to a processor in a laptop or

electronic device or it could refer to a food processor. (this was the example

given in class). So when is it appropriate to link these two completely

separate fields and when is it not appropriate to do so? Here, USPTO is saying

that we need to consider the problem being solved when making the connection.

Another related guideline is: "Analogous art is not limited to references

in the field of endeavor of the invention, but also includes references that

would have been recognized by those of ordinary skill in the art as useful for

applicant's purpose".

When it comes to

learning more about obviousness, I think these tables are a good place to

start-- so definitely take a look at them!

Assignment 7, Blog Post 1: Narrow Range versus Broader Range

For this week's blog

posts, the theme is obviousness. I wanted to discuss an article from

Patentlyo.com titled, "Whither Obviousness: Narrow Range Anticipated by

Broader Range in Disclosure" by Dennis Crouch. Consider an invention "that is anticipated, but

likely not obvious. According to the apellate panel, the prior artfully

discloses and enables the invention but also teaches that the proposed

invention is impractical and does not work well." [1] This is part of a

classic hypothetical case presented in law schools.

The patent that we

are considering is given in link [2] below. This patent protects a process for

clarifying water using a flocculated suspension of aluminum and quarternized

polymers. The patent owner and inventor, Richard Haase, has filed more than 50 patents

on water purification/ energy and is the CEO of ClearValue. Pearl River, who

was once a customer of ClearValue, later began making its own patented process. Haase sued them for patent

infringement and for trade secret violation. The conclusion is that "a

broad range disclosure found in the prior art ("less than 150 ppm")

anticipates the narrower range found in the claims ("less than 50

ppm"). Under 35 U.S.C. § 102, "a claim will be anticipated and

therefore invalid if a single prior art reference describes 'each and every

claim limitation and enable[s] one of skill in the art to practice an

embodiment of the claimed invention without undue experimentation'"[1]

The Federal Circuit

addressed a similar situation in the 2006 Atofina decision, in which there was

a narrow claimed temperature range and the prior art dictated a broader

temperature range. At that time, the final decision was that the broad range

disclosed in the prior art did not anticipate the narrow range claimed later.

Instead, it was agreed that there was something significant about the claimed

temperature range. However, in this case, the court ruled that "the narrow

range is not critically different from the broad range….[and] that the claimed

narrow range was fully disclosed by the broad range and therefore is

unpatentable."[1]

Okay, so how does

all this relate to obviousness? The article states:

"The mechanism that the court used to

distinguish this case from Atofina is very much akin to obviousness

principles-- looking essentially for synergy or unexpected results that make

the narrow range qualitatively different from the broad range" [1]

Take a look at the

article and actual patent if you are interested in learning more about the

case! (see links below)

Friday, March 7, 2014

Assignment 6, Blog Post 2: Bioprinting Patents

So, my last blog

post was on 3D printing technology in general, and I somewhat focused on the

stereolithography part since some of those patents were expiring very soon-- in

the next five days! I wanted to stick

to a similar topic for my second blog post this week, and wanted to talk about

3-D printing in tissue engineering applications. Usually, there are many

arguments with patents that are in the health and biology area (such as patents

on genetic sequences), because it is important to differentiate the human

innovation versus something made by nature.

The article I read

is titled, "A Look at The Patentability of 3-D Printed Human Organs".

Bioprinting is the intersection of 3D printing and inkjet printing to print

layers of living cells. Multiple layers of cells are stacked within a gel-based

material to form functional living tissue. As a bioengineer, I think this is

really interesting and exciting area. As of today, scientists have already

created functional 3D human blood vessels and mini-livers using this

technology. There is also the potential to generate entire human-sized living

organs (although there are some scientific challenges to overcome that I won't

get into here-- but feel free to ask me in person!).

In class, we all

have learned that patent protection is extremely important, for it allows

inventors to fully capitalize on their investment, by discouraging or delaying

competition. In this blog, I wanted to focus on some issues related to

patenting artificially created living human tissue. The patent office and Congress rule that

patens on human organisms are not eligible for patent protection. However,

according to the article, inventors have successfully been able to "obtain

protection for genetically engineered animals by narrowing the claim scope to

'nonhuman' subjects" [1]. One

example of this is U.S. Patent No. 8,088,968, which claims:

"a

'non-human mammal' with a particular genome composition where the nonhuman

mammal is a mouse. A 'tissue' of such nonhuman mammal is also separately

claimed."

Also, it is

important to note, that while the above is deemed patentable, the USPTO has

rejected patent claims on a human embryo under 35 U.S.C. Section 101 and also

because it violates Section 33(a) of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act.

Back to bioprinting

human organs. The previous argument was for patenting animals other than

humans. What are some arguments in favor of patents for bioprinted organs?

"Rather

than viewed as products of nature, bioprinted organs and tissue may be

considered to be manmade living materials artificially arranged in accordance

with a particular printing geometry that facilitates any naturally occurring

cell behavior"[1].

One similar example

is U.S. Patent No. 8,394,141, which includes claims directed to an implant

created from "fibers of defatted, shredded, allogeneic human tissue"

such as "tendon, fascia, ligament, or dermis" and further including a

"growth factor" (which helps in the differentiation of cells to the

desired cell type). Allogenic tissue is basically tissue not from the same

individual (which would be autologous), but from the same species. Thus, if

patents on tissue-

engineered implants

are allowed, so should patents on bioprinted organs.

So, what do you guys

think? Do you think patents on bioprinted organs should be allowed or not?

Please respond in the comments below!

Thursday, March 6, 2014

Assignment 6, Blog Post 1: Patents in 3D Printing

This topic was

actually brought up (quite randomly actually!) by a friend of mine recently. He

works at the machine shop at UC Berkeley, and he mentioned how in 2009, the

patent on the 3D printer expired and how everyone started delving into that

market, since it was so lucrative. Soon after, smaller desktop 3D printers came

out. Thus, I decided to look into it.

According to an

article written by John Hornick and Dan Roland on a few months ago, 3D printing

is a 30 year technology that has recently starting entering the mainstream, but

has not yet become commonplace. Hornick and Roland questioned what is holding this

industry back? Some people argue that patents have held back innovation in 3D

printing technology, because the companies are worried about getting sued, so

they do not spend the resources to develop the technology. This in turn,

reduces competition, keeping prices high and creating barriers to discourage

others from entering the market. Other people argue that this is not actually

the case, and what is holding 3D printers from becoming more commonplace is

that the printers are too slow and cumbersome. "Regardless of where one stands in this debate, the threat

of a lawsuit is certainly real and the 3D Printing Patent Wars, like Smart

Phones Wars, are probably not too far down the pike." [1]

Link 1 below is a

very good website to go to for a summary on the key 3D printing patents. Some

of them have expired last year or beginning of 2014, but there are still many

more that are expiring this month, as well as the next coming months (as well

as some in 2015). I just wanted to spend some time talking about the patents

that will expire soon and how this will affect the 3D printing industry in

general.

There are several

patents that are expiring in just the next few days (on March 11th):

Patent 5,609,812 is

titled, "Method of Making a Three-Dimensional Object by

Stereolithography". This is for making a 3D object from a medium that will

soilidify after exposure to synergistic stimulation, such as ultra violet or

infared radiation. While stereolithography is a very common invention, this

method improves on it by allowing to identify an endpoint of the first vector

and the beginning of the second vector (the vectors define the pattern of

exposure). The invention also comprises a method for scanning at a fixed

velocity along the first vector and mechanically blocking the UV or IR.

Patent 5,609,813 is

also titled "Method of Making a Three-Dimensional Object by

Stereolithography." This goes back to what we discussed in class this week

on how mulitple patents can have the

same name. However, since patents talk about innovation, their claims must be

different. This patent protects a method of applying a layer or flowable

material, generating and sequencing the pattern of exposure paths for the

layer, and exposing these paths to the UV/IR radiation according to the

sequence. To me, this sounded really broad at first, but I'm sure there are

more details that can easily be discerned by someone who is knowledgeable in

the area.

Patent 5,610,824 is

titled, "Rapid and Accurate Production of Stereolithographic

Parts". This patent protects an apparatus and a method for the same type of

process talked about in the first two patents. We also discussed in class what

can be patented (basically anything made by man). While the previous two

patents protected methods (or processes), this patent protects both a product

(a container with the medium) and a method (generating a beam of radiation).

Here, what is different is that the beam of radiation has different first and

second intensities and thus the two lines are scanned at different intensities.

This is useful for large and complex objects, because the laser can be directed

over portions of the material without curing a significant amount.

A patent that I am

interested in is expiring June 2nd of this year. This patent (No.

5,503,785) protects a process for

producing 3D objects having overhanging fragments freely suspended in space. I

believe that once this patent expires, many others will come into the market,

since it is a huge space.

The article

concluded by saying that it is unknown "when the major battles of the 3D

Printing Patent Wars will begin. New laws, evolving technology, and an

unpredictable economy might affect 3D printing more than any of these patents.

Thus, if would be imprudent to say that the expiration of one or more of them

is the key to growth because the market can dictate otherwise."[1]

Saturday, March 1, 2014

Assignment 5, Blog Post 2: Patent War in Pharmaceutical Industry

Since I find the

patent wars in the pharmaceutical industry particularly interesting, I decided

to focus on that topic this week. I find patents on drugs interesting due to

the huge amount of funding and time needed to even get a drug into market.

According to forbes.com, the average cost of bringing a new drug to market is

$1.3 billion. To put this price in perspective, 1.3 billion dollars would allow

a person to buy 371 Super Bowl ads, 16 million official NFL footballs, two

pro-football stadiums, almost all NFL football player's salaries, and every

seat in the NFL stadium for six weeks in a row.

The drug developed by major pharmaceutical companies costs between $4

billion to $ 11 billion.[2]

This is an example

of patent war with another popular company in the Bay Area-- Bayer, which has a

manufacturing center located in Emeryville (although its headquarters is in

Germany). Bayer was battling Pharma Dynamics, a Cape Town- based generic drug maker.

I learned that Bayer is called the "evergreening" of pharmaceutical

patents, meaning that they make small changes to existing products in order to

extend their patent protection and keep makers of cheaper generics out of the

market.

On March 2011,

Pharma Dynamics obtained registration from Medicines Control Council (MCC) for

Ruby, a contraceptive drug. Ruby was a generic version of Yasmin, a drug that

was still under patent protection by Bayer. Pharma Dynamics believed that the

Yasmin patent, which was granted in 2004, was invalid and applied to revoke the

patent, after obtaining approval from the Medicines Control Council (MCC) to

sell Ruby. The company claimed that "the Yasmin patent lacked 'novelty'

and 'inventiveness' because Bayer had already patented the product in

1990." This would mean that the patent expired in 2010, since the standard

practice, followed internationally, calls for 20-year protection. This 20-year

period is set to allow the inventor to compensate for their investment and make

a profit before other competitors can copy them. The business development

director of Pharma Dynamics', Tommy Scott, said that the company waited for the

Yasmin patent to expire, and wasn't aware of the second patent issued in 1999.

Bayer claimed that this patent was original, because it contained an active

ingredient that allowed the drug to dissolve faster.

It seems that there

have been growing patent disputes in many developing countries, as companies

try to bring down the cost of medicine by promoting generic versions, normally

termed "incremental innovation" by research-based companies. Competitors

argue that by doing this (filing several patents on discoveries made years

ago), the original inventors limit competition.

Assignment 5, Blog Post 1: Patent War in Pharmaceutical Industry

Genzyme Corporation

is a company based in Cambridge Massachusetts, and Genentech (which many of you

probably have heard about) is headquartered right here in the bay area in South

San Francisco. These two companies filed lawsuits against each other over a

clot-breaking agent for heart attack patients.

Genzyme had a 1994

patent for a chemical produced through genetic engineering of DNA. The company

claimed that Genentech's TNKase "clot-busting" product infringed this

patent. This dispute was mainly focused

on "whether payments were due under a license Genzyme had granted to

Genentech" according to William Marsden Jr., the Genzyme lawyer.

Genentech then sued

back in 2001, asserting that the technology they use is different, hoping that

the court would rule that the patent didn't cover the product or that the

patent was invalid.

Here is another similar case with a different drug (t-PA) that I found even more interesting: Toboyo is a four

billion dollar textile and pharmaceutical maker, which is involved in making

the t-PA drug, under license from Genzyme. In late 1991, Osaka District court

bailiffs decided to confiscate the drug at the Toyobo plant in Japan, because

Toyobo's sale infringed Genentech's Japanese patent. What I find extremely

interesting about this case, especially from a patent's perspective, is that

"Royalties from the drug's sales in Japan were not expected to make major

contributions to revenues at either Genentech or Genzyme, but the case was

called significant because of its implications for patents in Japan…[for] the

case was the first seizure of a product by Japanese authorities to protect a

biotechnology patent". G Kirk Raab,

the Chief executive of Genentech, said that "It's a strong affirmation on

the part of Japan's judicial system. It says to the biotech industry that

strong patents will be supported by Japanese courts". Unfortunately, this

decision was bad news for Toboyo, because t-PA was one of Toboyo's first major

pharmaceutical and the company had invested in establishing production

processes and marketing scheme for t-PA.

Friday, February 21, 2014

Assignment 4, Blog Post 2: Battle between St. Jude Medical and Volcano Corporation

St. Jude Medical and

Volcano Corporation have been fighting a legal battle over patents related to

pressure wire technology in cardiac care. The argument started when St. Jude Medical sued Volcano in the Delaware district court

for infringing five St. Jude patents on pressure guide wires, which are long,

thin, and flexible wires used by cardiologists to insert into a patient's blood

vessel during surgery, such as angioplasty. Angioplasty is basically a surgical

procedure used when a patient's blood vessel gets clogged with plaque. A

balloon is used to swish the plaque to the sides and a stent is placed to keep

the plaque from blocking the blood flow. The pressure wires use a microscopic

pressure-sensing chip that is used to measure fractional flow reserve, and thus

allowing a cardiologist to determine how severe the blockage in the artery is.

Then Volcano

counterclaimed and said that St. Jude had infringed four of its patents.

Volcano later dropped one of the four patents from the lawsuit. On October

19th, 2012 the jury decided that Volcano did not infringe two of St. Jude

Medical's patents and that the other two patents were invalid.

On October 25, 2012,

in response to Volcano's counter claims, a jury of eight ruled in favor of St.

Jude, saying that Volcano had not shown infringement of its patents.

After reading this

article (as well as the Nova article listed below), I want to look into what

factors made some of the patent infringement claims invalid I also want to

learn more about the process of making a counterclaim as well as reaching a cross licensing or royalty

agreement. It would also be good to look at the original patents and trying to

dissect them myself.

Assignment 4, Blog Post 1: Nova against Medical Device Giants

This week, I chose

to do a topic of my choice (with professor's approval, of course). The topic I

chose is patent wars in the medical device industry.

I read an article

titled, "Going Toe to Toe With Medical Device Giants". Abbott

Laboratories, Roche, and Medtronic claimed that Nova Biomedical (a company that

makes blood-testing equipment for diabetes) infringed on their patented

technology. Nova only had $165 million in revenue, so the company really

couldn't afford battling the case legally. However, interestingly, the CEO,

Francis Manganaro, decided to battle it anyways, noting "My partners and I

decided we would rather go down with the ship and lose the company than to give

in to people who behave like that". I definitely think it takes courage

and guts for a CEO to make a decision like that!

Nova's home glucose

meter is a cellphone-size device that digitally displays the blood glucose

level from a drop of blood. By late 2010, Nova had spent $31 million defending

itself. When all these large companies sued Nova, Nova had to take the burden to prove that

they were innocent. However, making that case can cost up to $10 million, and

much of that is factored in before a trial even begins. Because of this, many small companies don't try defending

themselves.

Manganaro launched

Nova with six partners in 1976. The company first made tabletop blood-testing

machines used in ICUs (intensive care units). Their hand-held blood glucose

reading device for home use came to market in 2003. At that time, it required

only 300 nanoliter of blood and took in five seconds to make a reading.

Handheld meters are an $8 billion market-- while the individual meters are sold

for 20 dollars, most of the money comes from selling replacement test strips on

which the drop of blood is placed.

In 1997, Chung Chang

Young and Handani Winarta improved the glucose meters using laser etching to

allow the device to use even smaller amounts of blood. Nova made a deal with BD (Becton Dickson) to

distribute the meter under its own name (BD Logic Meters) In Spring of 2003,

Therasense, a small company that made diabetes tests, claimed that the meter

infringed two of their patents. The situation got much worse for Nova when

Therasense was bought by Abbott for $1.2 billion. The case later expanded to

involve four Abbott patents. First, Manganaro tried to negotiate a cross

license or royalty arrangement. BD struggled to compete with Abbott and Roche

and thus decided to leave the glucose monitoring market. This left Nova to find

another distributor.

Also, when Manganaro

tried to reach a settlement with an Abbott executive, the executive basically

told Nova that he would let it all go if Nova left the glucose monitor business

and gave the technology to Abbott.

In 2007, Roche sued

Nova for infringing two of its patents, and while Roche says that "Nova's

size had nothing to do with this lawsuit", Manganaro believes that the

purpose of this law suit was to get rid of Nova.

Then, in February

2008, Medtronic sued Nova for theft of its trade secret: "the mechanism

Nova used to communicate with Medtronic's insulin pump"

The result is as

follows: In 2008, federal judges invalidated parts of two Abbott patents and

declared that Nova did not infringe the third patent. The fourth patent was

declared invalid. In September 2009, LA jury ruled that Nova had not stolen any

of Medtronic's trade secrets.

Friday, February 14, 2014

Assignment 3, Blog Post 2: Google Sold Motorola to Lenovo

So why did Google

sell Motorola to Lenovo? There are many different opinions about this. Here are

some: According to Sascha Segan, Google's mobile strategy is to get Android

onto as many phones as possible. Unlike Apple, BlackBerry, and Microsoft, most

of Google's revenue comes from advertising. This includes that on mobile

devices. Once Google bought Motorola, some of Google's major licensees started

developing or buying their own non-Google operating systems, because they were

concerned that Google would compete directly with them. Examples include Samsung with Tizen and LG

with WebOS. However, after selling Motorola, Google can be a neutral broker of

operating systems, and thus, make money. Futhermore, Google never made any

money from Motorola.

So now, the question

arises why Lenovo bought Motorola. Several reasons for this. First of all,

Lenovo is the top three smartphone maker, according to data from Gartner (Nov.

14, 2013). United States has one of the world's largest smartphone markets (which

does not come as a surprise). However, Lenovo's marketshare in the United

States is extremely small-- nearly zero. Lenovo's main business is in personal

computers, but unfortunately, its PC sales aren't growing. According to the

article I read, Segan's opinion was that, "if Lenovo is going to be a

technology leader in the late 2010s, it needs to be a mobile tech leader.

[Thus], assembling a global smartphone business is key."(Seegan 2014).

Furthermore, Lenovo has experience integrating and managing technologies based

in the United States. For example, Lenovo bought ThinkPad from IBM and made it

successful. According to the article, getting into the U.S. market is heavily

dependent on the relationships with U.S. carriers, ad Motorola's has developed

some really good relationships, such as

the Droid deal with Verizon Wireless. Since this transaction occurred pretty

recently, we will see how Lenovo fares!

Assignment 3, Blog Post 1: The Time when Google Bought Motorola....

This week's

assignment is to discuss why Google bought Motorola and then sold it soon

after. This blog post will focus on the former (why Google bought Motorola),

while the next blog post will focus on the latter.

Google announced the

acquisition of Motorola Mobility on August 15 for $40 per share. So the

question that naturally arises is why

did Google decide to buy Motorola? Google bought Motorola for the patents,

because Motorola had a huge patent library that could be used defensively.

Google also announced that together, both companies "will accelerate

innovation and choice in mobile computing" and that "Motorola

Mobilitiy's full commitment to the Android operating system means there is a

natural fit" between the two companies [2]. They also mentioned that they

plan to run Motorola as a separately operated business, so that each party

focuses on what they do best. In January 2011, Motorola Mobility (the former

Mobile Devices division of Motorola, Inc.) split from Motorola, Inc. Motorola Mobility holds at least 24,000

patents and pending patent applications worldwide, and approximately 5,000

patents and 1,500 pending patents in the United States. The article I read of

patentlyo.com was published in August of 2011 by Dennis Crouch, a Law Professor

at the University of Missouri School of Law.

Sources:

Friday, February 7, 2014

Assignment 2, Blog Post 2

I read

this article published on November 1st, 2013, titled "Patent Wars: Tech

giants sue Samsung and Google".

Rockstar Consortium is a group of tech giants (Apple, Microsoft,

Blackberry, Ericsson, and Sony). Rockstar recently spend 4.5 billion dollars

buying Nortel patents. Nortel was a telecommunications and data networking

equipment manufacturer. My first

reaction was "that is a LOT of money"-- we are talking billions (not

millions). It was also interesting to learn that, in the third quarter of 2013,

Android devices accounted for 81.3% of smartphone shipments, while Apple iOS

was 13.4% and the Windows phone was 4.1% (statistics from a research firm called

Strategy Analytics). I had thought that the Apple iOS would make up a greater

percentage, but I realized that these statistics are solely for shipment in a

span of four months.

I also

read about how Nokia (whose mobile devices division is now bought by Microsoft)

won a patent victory over HTC. The HTC One smartphone was banned from import

into the UK. (Interesting, because I own an HTC One!) Also, in October of 2013,

Samsung promised to cease taking rivals to court for alleged patent

infringements for a period of five years. There is a $18,3 billion dollar fine

if they breach European anti-trust laws. Again, the severity of the fine (the

huge sum of money!) amazes me. Samsung and Apple are in the courts of more than

ten countries across Europe.

The

articles I have been reading have made me more interested to look into whether

or not there are avenues for cross licensing, so that people can share the

technology and products turn out better overall.

Assignment 2, Blog Post 1

Hi all!

I actually do not have too much background knowledge about the mobile patent

wars, but I am excited to learn more about them! I think what makes them so

interesting is that we are so familiar with the technology, since everyone owns

a cellphone.

Patents

are useful because they give the inventor recognition for discovering something

that has never been discovered before. Thus, they should be used as a tool to

help move invention forward by motivating people to work faster so that they

can apply for the patent first.

However, from the conversation in class and the articles I

have been reading, the mobile patent wars are actually hurting innovation.

Professor Lavian mentioned in class that Apple and Samsung are involved in 22

different lawsuits in different courts. To stall the process and to prevent

other companies from implementing new inventions in their products, companies

will hire lawyers to sue on literally anything. I read this one article, which

was published in October of 2012 (link: http://www.infoworld.com/d/the-industry-standard/mobile-patent-wars-hurting-innovation-experts-say-205074). A technology lawyer, Marvin Ammori, reached out to

Congress to stop patents for software and business methods.

This reminds me of a certain scenario that I encountered on

a popular T.V. show called Shark Tank. On the show, entrepreneurs are given the

opportunity to pitch their ideas to a panel of investors. One entrepreneur was

pitching a product, and he mentioned that he had a patent on holes/ tubes in

clothing where you can insert wires and other gadgets (such as from earphones/

mp3 players, etc). [It may be similar to this one: http://www.faqs.org/patents/app/20130019377]

I believe he mentioned that he had a

patent on this broad category, and one of the investors exclaimed that because

there are so many patents on very simple ideas, it is difficult for other

entrepreneurs to make sufficient progress.

I also

read about the America Invents Act, a patent reform bill that was passed in

September of 2011. This act basically switched the system from a "first to

invent" to "first to file". I look forward to learning more

about how this law affected other patents on mobile devices.

Thursday, January 30, 2014

Assignment 1, Part 2: Reason for Taking the Class

As a bioengineer, I

am exposed to many different areas of engineering. Bioengineering is very

diverse field, and it can include a little bit about mechanical engineering,

electrical engineering, materials science, etc.

I am passionate about innovation in the medical devices and healthcare

fields. Last semester, I worked with a team to prototype a design for

noninvasively measuring venous oxygen saturation, which is the percentage of

oxygen in the blood after your body has used up as much oxygen as it can (so

basically, right before it goes back into the heart/ lungs). Currently, the

gold standard for doing this is using a catheter and sampling the venous blood.

However, catheterization is invasive and takes about 30 minutes to an hour to

insert. Also, once the blood is sampled, it needs to be taken into the

laboratory for analysis, which adds to the time required to provide results.

Thus, my team researched possible alternatives to find this value noninvasively.

We also built a prototype to test out our ideas. As an engineer, I will be

working with a team to invent medical devices. Thus, I felt that taking a

patenting class in college was a good way to start learning about the process

of protecting one's intellectual property. I am excited to learn more in the

class! Looking forward :)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)